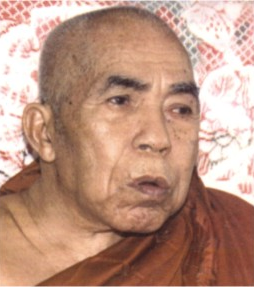

I just learned from the Daily Star that the Venerable Sadhanananda Mahathera has died. He was the most revered Buddhist monk in Bangladesh, commonly considered to be an arahant. Like many others, I always referred to him as Bono Bhante, his nickname in the local Chittagonian dialect, a name which translates literally as “Forest Monk.”

If you remember Luangta Maha Bua, you can probably get a sense of how important Bana Bhante was to Bangladeshi Buddhists. He was of the Chakma people, an ethnic minority, and had a reputation for clear, incisive and straightforward speaking. Many of his years in the monkhood were spent practicing in the forest. He lived into his nineties, having witnessed his native Chittagong occupied under British colonialism, partitioned into Pakistan, and thrown into turmoil following Bangladesh’s liberation. He was ordained for 63 years, and he was a widely-respected living Buddhist institution in a majority Muslim nation.

When I was much younger, I had dreamed of traveling to the beautiful Chittagong Hill Tracts to pay my respects to Bana Bhante. It seems now the best donation I can give is to share his story with you. You can read his biography online. You can also download an English-language book of his sermons, thanks to a contributor on Dhamma Wheel.

If you’ve never heard of Buddhists in Bangladesh before, you can read more in other posts I have written on the topic. I especially encourage you to learn more about the struggle for self-determination of the Chakma people in Chittagong. As I wrote before…

Bangladesh’s Chittagong division is home to a large number of Buddhists, including the meditation masters Dipa Ma and Anagarika Munindra. These teachers in particular had a profound impact on Buddhism both in the West and elsewhere in Asia far beyond their native Chittagong. The Buddhists of Bangladesh, however, have no Dalai Lama or Aung San Suu Kyi to direct the world’s attention to their plight. They pursue their quest for liberty and justice largely in the shadow of the world’s attention.

And now they have lost one of their most venerated Buddhist leaders.