I am not a Pure Land Buddhist. My familiarity with Pure Land Buddhist traditions is rather limited, but I know enough to know that Douglas Todd’s Vancouver Sun article on Buddhism in Canada (“As Buddhism grows, two ‘solitudes’ emerge”) distorts the tradition to the point of stereotype. Todd depicts Pure Land Buddhism in Vancouver as a bunch of Asian Buddhist immigrants who don’t speak English and whose superstition-dominated spirituality consists of liturgical appeals to be reborn in a Buddhist heaven.

Pure Land is one tradition among many within Mahayana Buddhism, such that most of Vancouver’s Chinese Buddhist temples practice Pure Land Buddhism alongside sutra study, meditation, community service and non-Pure Land recitation practice. It is a cavalier misrepresentation of these temples’ Buddhist traditions for Todd to reduce all they do to the pursuit of a heavenly rebirth. Even Jodo Shinshu Buddhists, who focus more exclusively on Pure Land philosophy, aren’t just sitting around praying to be saved.

Take a look, for example, at Dharma Realm Buddhist Association, the organization of Ven. Heng Jung, who was the only Asian Buddhist whom Todd quoted. It’s more than just Pure Land. You will find Pure Land Buddhism practiced alongside scholarship, meditation, recitation and much more. Online, you can read the Dharma Forest blog and watch videosof Ven. Heng Sure, where you will find quite a bit more than repetitions of “Amitabha.” You could also check out the dharmas blog of Dharma Realm Buddhist University, where the vast majority of posts appear to be on subjects unrelated to the Pure Land.

Other Buddhist groups dominant in the Chinese Canadian community, such as Fo Guang Shan—the same organization that founded Rev. Danny Fisher’s employer—proudly promote both Pure Land and Ch’an meditation practice. There is even a diversity of views within these communities as to what the “Pure Land” means. “Many Pure Land practitioners today tend to stay clear of ‘the Pure Land exists’ idea and settle for Pure Land being in one’s own mind,” Ven. Zhi Sheng, a white Pure Land Buddhist, writes. “Pure Land practice is not just about being re-born in a lotus bud in the Land of Ultimate Bliss to live happily ever after. One will have missed the point completely.”

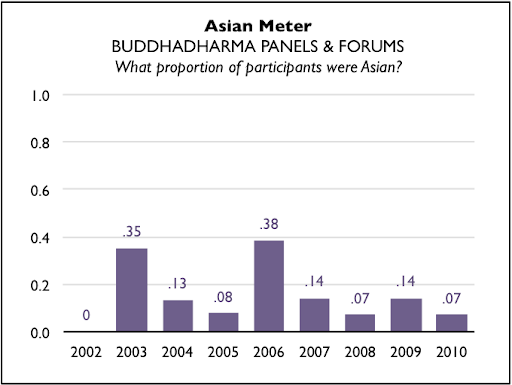

Most sadly, Todd missed out completely on Vancouver’s Jodo Shinshu community, one of the oldest in North America. If Todd had cared to sift through Tricycle and Buddhadharma online, he would have found Revs. Tai and Mark Unno, Rev. Patti Usuki and Rev. Jeff Wilson talk about some of the very misconceptions of this Pure Land Buddhist tradition, which apparently were too enticing to avoid. There are quite a few other Jodo Shinshu perspectives online, such as Rev. Patti Nakai’s Taste of Chicago Buddhism blog or Rev. Harry Bridge and Dr. Scott Mitchell’s entertaining and illuminating Dharma Realm podcast, where they wrestle with questions from “What is Shin Buddhist practice?” to “Is Shin Buddhism in America really declining?”

Note that none of the individuals mentioned here who follow Pure Land Buddhism are Asian Buddhist immigrants who don’t speak English—many are, in fact, Western converts.

While I have no doubt that there are Buddhists in Vancouver who will readily identify as Pure Land Buddhists and others who avow a yearning for rebirth in the Pure Land, for at least as many the Pure Land tradition is just one in a knapsack of Mahayana Buddhist traditions that an individual may practice. The Pure Land “practice” itself varies, just as practitioners have different perspectives on what the “Pure Land” actually is. You can learn more about Pure Land Buddhism by following the links above—I am by far no authority on this subject—however, from Todd’s article in the Vancouver Sun, you will find a stereotypical perspective of the type that Pure Land detractors would promote.