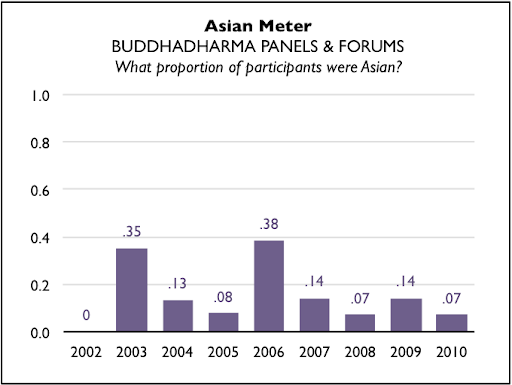

There is little new to say that I didn’t already say five years ago.

Let me start out, as I normally do, by noting that there are many virtues to the Buddhadharma discussion, “Making Our Way: On Women and Buddhism.” Sandy Boucher, Grace Schireson, Christina Feldman, Lama Palden Drolma and Rita Gross are individuals with considerable experience examining and debating the topic of women and Buddhism. They have wonderful insights to share, many of which I highlighted and jotted down in my notebook. But as you might have guessed, I noticed something missing.

Namely, Asians.

What makes this conversation so dangerous is that it easily leaves readers with the belief that Asian women, be they in Asia or the West, don’t even think about this topic, never mind do anything about it. Several years ago I posted Cheng Wei-Yi’s essay, “Rethinking Western Feminist Critiques on Buddhism,” and one of the comments came from someone with this very impression:

The critique is that we’re not listening to Asian women’s input here; well, then let’s have more of it. What developments towards the equality and dignity of women have taken place in Buddhism, apart from “western” feminist influence?

It is in response to challenges like these that Rev. Patti Usuki wrote Currents of Change: American Buddhist Women Speak Out on Jodo Shinshu. If you read the blog of Rev. Patti Nakai, you can find yet another Asian American Buddhist woman’s thoughts. Or you can read other publications by Cheng Wei-Yi. In a previous letter to Buddhadharma, I included a list of several Asian Buddhist women, including published authors, who could speak to this topic. Not only can you find their thoughts in books and on websites—these women are alive. You can send them email.

I have spent my whole life around Asian Buddhist women in the West. They are the reason I am Buddhist. They have taught me how to bow, how to chant, how to apply Buddhist teachings, how to walk mindfully, how to meditate and delve into deep concentration. These amazing women don’t fit any of the stereotypes of Asian Buddhists. I have known Asian American nuns ordained in the Tibetan, Mahayana and Theravada traditions—women who have had unthinkable struggles, incredible stories and strong opinions on the role of women in Buddhism.

Just imagine how different a conversation you would have if you gathered these women together for a discussion on Buddhist patriarchy. It’s something that’s never before appeared in Buddhadharma or Tricycle. Imagine what it would be like if they wer犀利士 e in the room, so that you couldn’t so easily refer to Asian Buddhists as “them.”