More travel means I probably won’t get to write all that I planned to write until this coming weekend. There are some wonderful posts and comments that I would love to respond to, but work and sleep are monopolizing this week’s schedule. Still, one old half-written post at the bottom of my draft box seemed more timely than ever—it included only a few words another blogger wrote two years ago, worth reposting:

If you’re going to claim an interest in social justice issues and then blindly look the other way when your own, fellow American Buddhists of different colors, genders, or sexual orientations are crying out, are suffering, then you need to question your own motives, your own beliefs, before yelling at me for doing nothing more than pointing out the obvious suffering of others.

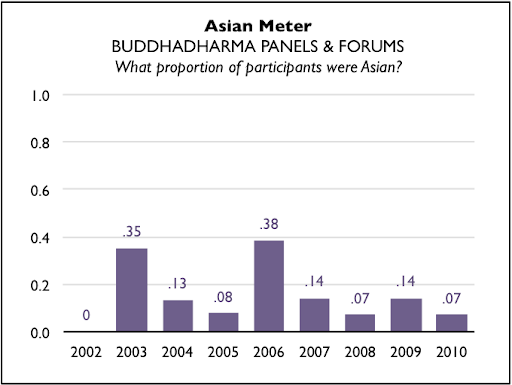

There has been a lot of work in the Buddhist community to address racial inequities in American Buddhism, but this progress feels limited. At least, that’s how it feels when today’s discussions don’t feel much different than those of yesteryear. Even so, I fully believe that there’s been real progress in the last ten years that simply may not be glaringly evident to the casual observer. Much work remains to be done, but what progress have you seen in reducing racial inequities in American Buddhism over the last decade?