After reviewing my interview with Maia Duerr, I noticed in the comment section an unanswered question, which I hadn’t read before.

Arun: can you provide specific examples of the marginalization and denigration of which you speak — and I don’t mean examples from 30 years ago, but current. I am partly wondering if there’s a mis-attribution occurring. Having spent quite a bit of time with Korean American Buddhists, it strikes me that their form of Buddhism really is very, very different than that which Westerners have been in the process of adapting for themselves, but just because each is different and each are drawn to different forms, doesn’t necessarily mean there’s marginalization or denigration.

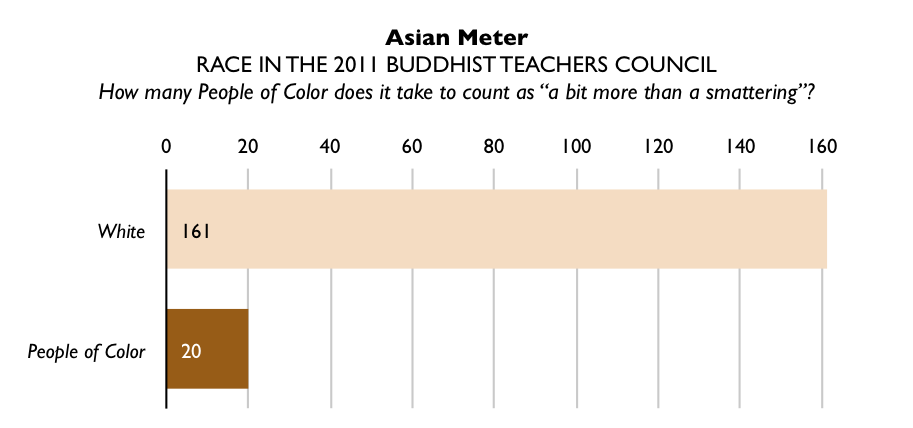

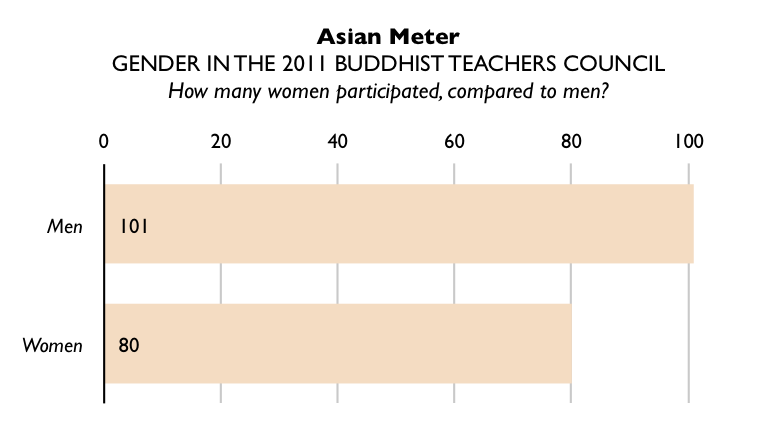

The most prominent examples of the marginalization of Asian Americans from the Western Buddhist narrative are found in high-profile Western Buddhist magazines, namely Shambhala Sun, Tricycle and Buddhadharma (the three largest by distribution). The paucity of Asian writers in these publications is well documented. A perfect recent example is Buddhadharma’s winter 2010 issue on women in Buddhism, “Our Way”, which completely left out the voices of Asian Buddhist women.

Another good example of our marginalization comes from the 2010 election, when the highest profile of the American Buddhist media swarmed around White candidates who didn’t identify as Buddhist, while ignoring the non-White candidates who did. It may have been twenty years ago that Tricycle founder Helen Tworkov wrote that Asian Americans “have not figured prominently in the development of something called American Buddhism,” but for many White Buddhists today, Asian Americans are still little more than an afterthought when “American Buddhism” comes to mind.

More subtle forms of marginalization include the ways that Asians are caged into stereotypes by the types of topics that Western Buddhist media choose to discuss with us. I recently demonstrated that while Buddhadharma typically allots just one or two spots for Asians on feature discussion panels, they make an exception for stereotypically Asian topics. The editors clearly know how to reach out to Asian Buddhists when they want to, but it seems that most of the time they are content with their almost exclusively White lineup of feature panelists.

Examples of our denigration are less frequent in published media these days, but abound online. During the firestorm over the Australian bhikkhuni ordination, Bhante Shravasti Dhammika lambasted Theravada Buddhists in Asia as “spiritually moribund, tradition-bound and retrograde.” I am still endlessly grateful to Bhante Sujato for standing upagainst accusations that misogyny in Western Buddhism is some by-product of Asian influence.

You need not dig too deep into the Buddhist blogosphere to find White-savior rhetoric or proposals to whitewash the face of Buddhism or White Buddhists who poke fun at Asian names. Beyond blogs, online forums host much franker assessments of “ethnic” Buddhists. (“They’re not really in the business of spreading the dharma.”) These words are far from the usual statements from Western Buddhist institutions, but they are part and parcel of the Western Buddhism that we Asians in the West must deal with.

When we complain about our marginalization, our complaints are repeatedly dismissed as invalid, divisive or even thrown back at us as examples of how we are lesser Buddhists. When the blogger Tassja wrote about White privilege in Western Buddhism, she was ripped apart with abusive language that I will not copy here. When my partner-in-crime Liriel wrote to Tassja’s defense by sharing her own personal story of growing up Buddhist in the West, she was called a racist and told that “it might be better to be a convert to Buddhism than to be born in to it.”

The examples here speak to the way that self-styled Western Buddhists use both online and print publications to craft a narrative of Buddhism in the West that marginalizes the voices of Asian Buddhists, who continue to constitute Western Buddhism’s largest demographic. Often, Asian voices are omitted altogether. The marginalization of our stories and perspectives results in a Western Buddhist media landscape where we are deprived of an effective rhetorical counterweight to the denigration of our communities, culture and Buddhist practice.

Our community is broad, including everyone from recent refugees to fifth-generation practitioners, from monastic teachers to social activists, and I would like to think that our lives are not so alien to those of Western Buddhism’s non-Asian practitioners that their publications are better off when we are pushed to the side.